When African Fashion Designs Go Mainstream

- Victoria Audu

- Apr 16, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: May 12, 2025

When I think about fashion and its relationship with the local industry, I immediately remember a scene from The Devil Wears Prada. You know the one. Andy is standing close to the door supposedly taking notes. Miranda is surrounded by an excited team suggesting hats, belts and jackets to compliment a look. One of them holds up two nearly identical blue belts and Andy sniggers. But her amusement doesn’t last long as in the following 2 minutes Miranda all but calls her a pawn in an industry she knows nothing about. Apart from the iconic nature of her retort, Miranda’s speech also taught me a thing or two about consumerism. Designs, colors and even complete outfits seen lining runways come to the streets either through watered down versions made by corporations who value money over art or small creators who are inspired by the avant-garde designs to create something similar. This is the trickle down theory.

In official terms, the trickle down theory describes the movement of excess wealth from the few at the top to the masses. In fashion, it’s the movement of designs from creators in fashion houses to mass production companies made more accessible to the public. High-end designers craft collections that set the tone for the industry, influencing mid-tier brands before finally reaching the everyday consumer through fast fashion or local adaptations. The dissemination process varies globally, shaped by economic structures and cultural dynamics. In Western contexts, luxury fashion houses debut styles that eventually filter into department stores and fast-fashion outlets. In Africa, where traditional craftsmanship intersects with modern fashion, the process is often more nuanced. The same aesthetics found in designer collections make their way to local tailors and artisans, who interpret them through their own creativity, materials, and cultural influences.

In the United States, trickle-down fashion is propelled by fast-fashion giants such as Pretty Little Thing and Fashion Nova. In Europe, it’s Boohoo and Primark that replicate high-end trends. The speed and efficiency at which these companies operate often results in harsh working conditions and underpaid staff. Their accessibility also ensures that styles seen on New York Fashion Week runways quickly find their way into the wardrobes of everyday consumers. Past runways, unique designs by brands like House of CB and Mirror Palais also trickle their way down from their original price point in the hundred of dollars to $20-$50. Unfortunately, so do creations by small creators who can only dream of the runway before their designs are snatched by these corporations.

However, in Africa, the replication process is not as rapid or industrialised. Instead of fast-fashion conglomerates mass-producing clothing, local markets thrive on reinterpretation. A dress that graced a Lagos runway may inspire the designs of street-side tailors, who, with their understanding of local tastes, produce variations that retain the essence of the original but incorporate practical adjustments for their clientele. This organic form of trickle-down fashion is further fueled by social media, where images of high-end pieces circulate widely, offering inspiration for both formal designers and self-taught creators.

A famous example is the signature Àdìrẹ pieces from Dye Lab. Dye Lab was launched in 2021 and they brand themselves as ‘small batch production craft brand exploring dyeing techniques to create products that offer a practical yet artisanal sensibility.’ Before Dye Lab came on the scene, Àdìrẹ, a technique of dying fabric to create different shapes and patterns, was largely considered something for special occasions. When they launched, Africans who were familiar with the technique, were introduced to a new way of making and using Àdìrẹ. Those who weren’t familiar with it were exposed to this technique in a mainstream way.

Signature items include Àdìrẹ bubus and xo co-ord sets that appeal to both the local and growing global audience eager to embrace African aesthetics. The brand’s popularity has grown steadily, with its designs appearing on celebrities, influencers, and everyday fashion enthusiasts who seek a mix of cultural authenticity and modern style. As a result, Dye Lab’s influence extends beyond its direct consumers, as tailors and smaller brands replicate and reinterpret its designs for wider accessibility.

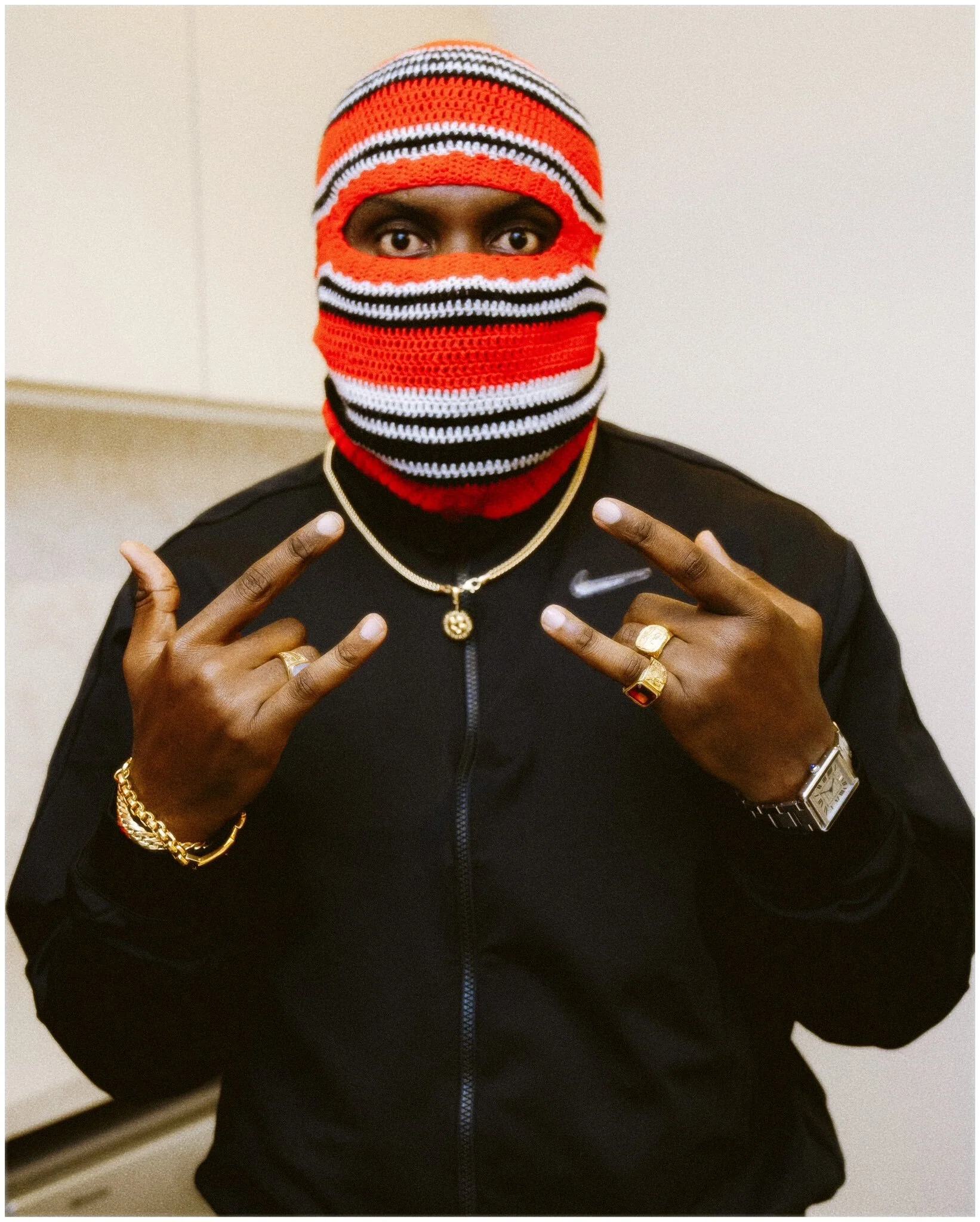

Similarly, Gaea Lumi operates within this ecosystem, though with a distinct focus on eco-conscious fashion. The brand was founded on principles of sustainability, seeking to counter the wastefulness of fast fashion by offering timeless, handcrafted pieces. Their signature piece, the OKPU AGU Bucket Hat is a staple piece for Nigerian rapper, Odumodublvck, an endorsement that propelled the brand into the limelight. In the crochet community, patterns pass around naturally and creators seek new designs to test out and make pieces for themselves. Since its launch, African crocheters have made similar patterns branding it the 'Odumodublvck Hat'. The major similarity of this seemingly normal design is in the unique colour scheme—red, white and black. However, what sets an original Gaea Lumi piece apart is its superior quality, precise fit, iron-engraved logo, and legally patented stitch pattern.

In a linear progression of this inspiration, British-Nigerian designer Ebele Ojechi's “For the Glory” collection reinterprets elements of traditional Nigerian heritage, such as the Isiagu balaclava, in a modern sportswear context. The Isiagu cap is a traditional Igbo accessory worn by chiefs, symbolizing status and authority. The collection blends these cultural symbols with global fashion trends–in this case crochet. Along with Gaea Lumi, Ojechi’s collection reinforces how African aesthetics are being continually reimagined across different fashion sectors, from streetwear to sportswear.

Mainstream audiences have always drawn inspiration from fashion houses and vice versa in a continuous cycle of innovation and expression. Vivienne Westwood was inspired by punk culture and took a niche interest materialised in safety pins, distressed fabrics and bold texts and turned it into a mainstream fashion statement. Dior was inspired by military uniforms and birthed the A-line silhouette that revolutionised fashion decades ago and is still relevant today. Similarly, Deola Sagoe revolutionised Nigerian Asọ-Ẹbí styles as we now know them by introducing laser cutting. This style has defined decades of Nigerian traditional wear since. In this same way, Dye Lab and Gaea Lumi have also been inspired by established local and global systems of Àdìrẹ making and knitting, designing, restructuring and popularising something new and unique. African online vendors, local tailors and young creators have also been inspired by these designs to create more affordable pieces for the masses.

This reverse is called trickle-up fashion and is evident in the way African streetwear and traditional textiles have influenced global fashion houses. Designers such as Thebe Magugu and Kenneth Ize have drawn inspiration from everyday African fashion, incorporating elements like Àdìrẹ , Aṣọ-òkè, and Kente cloth into their collections. The cycle of influence is fluid, demonstrating that creativity moves in multiple directions. African fashion is not merely consuming trends from the top down; it is actively contributing to global aesthetics, proving that the continent is both a receiver and a generator of style.

Beyond aesthetics, there are also economic and social implications of this fashion evolution. The trickle-down process creates demand for local artisans, tailors, and textile makers, reinforcing the value of homegrown craftsmanship and keeping money circulating in struggling economies. It also encourages conversations around sustainability as local production increases, reducing reliance on large corporations that encourage water waste and carbon emissions.

This approach fosters job creation, skill preservation, and community wealth, as materials are reused, up-cycled, and repurposed rather than discarded. This not only reduces textile waste, but also promotes a self-sustaining industry where designers, local artisans, producers, and consumers engage in a system that prioritizes durability over disposability. Additionally, local production diminishes dependence on imports, stabilizing economies and encouraging regional innovation. African designers and entrepreneurs are at the forefront of circular fashion, implementing business models that eliminate waste and pollution through avenues like okrika/mitumba (thrift) and local material production.

All in all, the trickle-down effect in African fashion is far from linear. It’s a complex intersection of inspiration, adaptation, and reinvention, where brands like Dye Lab and Gaea Lumi set the tone for a broader creative dialogue. Their designs don’t just filter down to the masses, they spark new interpretations that redefine the industry. As African fashion continues to gain global traction, it’s clear that the continent is not merely following trends but shaping them, proving that fashion’s life cycle is a continuous loop of influence and reinvention.

Join us in shaping the future of African fashion. Sign Up to become a part of the Clearly Invincible fashion community and for a consultation to aid your fashion entrepreneurship journey.

Fashion Services: Illustrations | Collection Planning | Portfolio's | Consultations

Comments